This post is a script of the talk that I've made on UIKonf'16. That was a first time for me to present on such a big conference and honestly I'm not even close to a public speaker so you may enjoy just reading it more. Anyway here is the video. And slides are here.

For many of us Swift opened up a world of functional programming. But it is still much more object oriented language than functional. And our main tools - Cocoa frameworks - are object oriented. So probably we ourselves will still keep writing object oriented code. The problem with that is that it is actually hard to write well designed object oriented code.

There are bunch of different design principles, like SOLID, KISS, DRY and others (YAGNI, RAP, CQS), and even more design patterns. Just the fact that there are so many different principles and patterns means, at least for me, that good object oriented design is hard, if ever possible.

Dependency Injection is itself not a part of SOLID principles that I have just mentioned. But it strongly relates to all of them. Unfortunately the concept of Dependency Injection is surrounded with many misconceptions.

Wikipedia gives us very complex definition:

"In software engineering, dependency injection is a software design pattern that implements inversion of control for resolving dependencies." - Wikipedia

And few more sentences... In contrast some developers say that dependency injection is just passing in an instance variable.

"Dependency injection is really just passing in an instance variable." - James Shore

Others think that it is some kind of voodoo magic that requires to use complicated and slow frameworks, or that it is only relevant for testing and just makes code harder to understand. I would say that all of these are misconceptions about Dependency Injection.

I will try to make it more clear, as far as I can, and show what I've learned about Dependency Injection. I will try to show how we can do Dependency Injection. And more than that how we should not do it.

Why Dependency Injection?

To start let's see what problems Dependency Injection tries to solve in the first place.

In programming we always have to deal with abstractions of different kinds and levels. They are just everywhere. Interfaces, methods, closures and even concrete types and variables names - they are all abstractions.

For a good code design it's very important to use proper abstractions because they make our code loosely coupled. That means that different componenets of our code can be replaced with alternative implementations without affecting other components. When our code is loosely coupled it becomes easier to test, easier to extend, easier to reuse, easier to develop in parallel. That all makes it easier to maintain.

Loosely coupled code is the main goal of Dependency Injection. It enables us to write loosely coupled code. And thus it makes testing, extending and reusing code much easier.

Very often Dependency Injection is discussed only in context of Unit Testing. And indeed it improves testability a lot, especially in Swift. But the real picture is much wider. If our final goal is not just unit testing some classes but loose coupling and making our code maintainable then we will need to make a bit more effort than just passing instance varibales.

Though it is true that in its essence Dependency Injection is about passing instance variables or better to say passing dependencies to their consumers. This is the first step and as each first step it is the most important one. But that is only one part of a story. There are also a second and even a third step. And these steps make the difference between just passing variables and Dependency Injection.

Dependency Injection Patterns

So let's start with the first step. There are few patterns how we can pass dependencies to their consumers:

- Custructor Injection

- Property Injection

- Method Injection

- Ambient context

Let's see how they look like using examples from Cocoa frameworks.

Constructor injection

Here is an example of constructor injection from CoreData:

class NSPersistentStore : NSObject {

init(

persistentStoreCoordinator root: NSPersistentStoreCoordinator?,

configurationName name: String?,

URL url: NSURL,

options: [NSObject: AnyObject]?

)

var persistentStoreCoordinator: NSPersistentStoreCoordinator? { get }

}Here the instance of persistent store coordinator is passed in constructor of NSPersistentStore along with some other parameters. Then reference to coordinator is stored and can not be changed in runtime.

With constructor injection we pass dependencies as cunstructor arguments and store them in readonly properties.

Though there are not so many examples of constructor injection in Cocoa frameworks, it is the prefered way to inject dependencies. Because it's the easiest one to implement, it ensures that dependencies will be always present and that they will not change at runtime what makes it much safer.

But there are cases when constructor injection is not possible or does not fit well. In these cases we should use property injection.

Property injection

This pattern is all over the place in any iOS application. For example delegate pattern is often implemented using property injection.

extension UIViewController {

weak public var transitioningDelegate: UIViewControllerTransitioningDelegate?

}Here for example view controller exposes writable property for transitioning delegate that we can change at any moment if we want to override the dafault behavior.

With property injection consumer gets its dependency through writable property that also has some default value.

Local & foreign defaults

Property injection should be used when there is a good local default for dependency. "Local" means that it is defined in the same module. nil is also a perfect local default, it just makes dependency optional.

When implementation comes from a separate module it is foreign. Then we should not use it as a default value. And we should not use property injection for such dependency. Instead we should use constructor injection.

Imagine that default implementation of transitioning delegate is defined not in UIKit, but in some other framework. Then we will always need to link to this framework even if we never use this API. UIKit becomes tightly coupled with that framework. And it drags along this unneded dependency. The same can happen with our own code and that will make it harder to reuse.

Comparing with constructor injection property injection is maybe easier to understand and it makes our API to look more flexible. But at the same time it can be harder to implement and can make our code more fragile.

First of all we need to have some default implementation in place or handle optional value in a proper way which can lead to cluttering code with unwrapping optionals. Secondly, we can not define our property as immutable. So if we don't want to allow to change it once it was set we will need to ensure that at runtime instead of compile time. Also we may need to synchronise access to it to prevent threading issues. For these reasons if we can use constructor injection we should prefer it to property injection.

Method injection

Next pattern, method injection, is as simple as passing argument to a method. For example here is NSCoding protocol:

public protocol NSCoding {

public func encodeWithCoder(aCoder: NSCoder)

}Each time the method is called different instance and even implementation of NSCoder can be passed as an argument.

With method injection dependency is passed as a parameter to a method.

Method injection is usually used when dependency can vary with each method call or when dependency is temporal and it is not required to keep reference to it outside of a method scope.

Ambient context

The last pattern - ambient context - is hard to find in Cocoa. Probably NSURLCache is the most close example.

public class NSURLCache : NSObject {

public class func setSharedURLCache(cache: NSURLCache)

public class func sharedURLCache() -> NSURLCache

}Here for example we can set any subclass of NSURLCache as a shared instance and then access it with static getter. And this is its main difference from singleton which is not writable.

Ambient context is implemented using static method or static writable property with some default value.

This pattern should be used only for truly universal dependencies that represent some cross-cutting concerns such as logging, analitycs, accessing time and dates, etc.

Ambient context has its own advantages. It makes dependency always accessible and does not pollute API. It fits well in case of cross-cutting concerns. But in other case it does not justify its disadvantages. It makes dependency implicit and it represents a global mutable state which is maybe not what you want.

So if the dependency is not truly universal first we should consider using other DI patterns.

Separation of concerns

As you may notice all these patterns are very simple and they share one common principle - separation of concerns. We remove several responsibilities from the consumer of dependency: what concrete implementation to use, how to configure it and how to manage its lifetime. This lets us easily substitute dependency in different context or in tests, change its lifetime strategy, for instance use shared or separate instances, or to change the way how the dependency is constructed. All without changing its consumers. That makes concumers decoupled with their dependencies, making them easier to reuse, extend, develop and test.

The obvious side effect of these patterns is that now every user of our code needs to provide its depnendecies. But how do they get them? If they create them directly then they become tigthly coupled with those dependencies. So we just move the problem to another place. This problem brings us to much less dicussed DI pattern called Composition Root.

Composition root

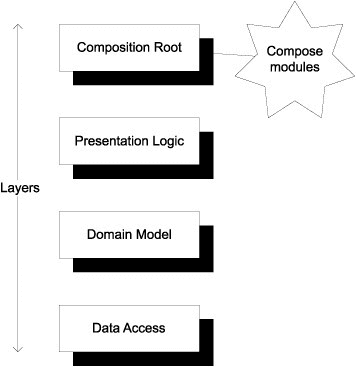

Composition Root is a place where components from different layers of the application are wired together. The main point of having composition root is to separate configuration logic from the rest of our code, do it in a well defined place in a common manner. Having a piece of code which single responsobility is to configure other components. Creating dependencies and injecting them in constructors or properties should be done only in the Composition Root.

Ideally there should be one Composition Root in the application and it should be close to application entry point. Like on this diagram. But it does not have to be implemented with a single method or a class. It can contain as many classes and methods as needed until they stay together at the same layer of components.

Here is for example implementation of Composition Root from VIPER example application.[2]

class AppDependencies {

init() {

configureDependencies()

}

func configureDependencies() {

// Root Level Classes

let coreDataStore = CoreDataStore()

let clock = DeviceClock()

let rootWireframe = RootWireframe()

// List Module Classes

let listPresenter = ListPresenter()

let listDataManager = ListDataManager()

let listInteractor = ListInteractor(dataManager: listDataManager, clock: clock)

...

listInteractor.output = listPresenter

listPresenter.listInteractor = listInteractor

listPresenter.listWireframe = listWireframe

listWireframe.addWireframe = addWireframe

...

}

}Here we have some root classes, root wireframe that only manages window root view controller and some separate components for some list of todo items, like presenter, interactor, wireframe. Then we just wire them all together. And it is all implemented in one class. And the only place where we use this class is the app delegate:

@UIApplicationMain

class AppDelegate: UIResponder, UIApplicationDelegate {

var window: UIWindow?

let appDependencies = AppDependencies()

func application(

application: UIApplication,

didFinishLaunchingWithOptions launchOptions: [NSObject : AnyObject]?) -> Bool {

appDependencies.installRootViewControllerIntoWindow(window!)

return true

}

}Here we first create dependencies class which will configure all of the components and wire them together. Then we just call a method that sets root view controller in a window.

So the entire objects graph will be created here with a single call and the only objects which will be created later in runtime are view controllers and views.

Unfortunatelly Composition Root is usually not discussed in articles or talks about DI. But it is probably one of the most important parts of Dependency Injection. If we manage to do that we have already come a long way.

The biggest challange of properly implementing DI is getting all classes with dependencies moved to Composition Root. - Mark Seeman

Anti-patterns

But as it often happens while we are trying to properly implement some patterns we can easily end up with anti-patterns. So, now let's move on to the dark side and see what are the common DI anti-patterns.

Control freak

The first one is control freak. That is simply when we don't use DI at all. When consumer of dependency controls how and when the dependency is created. It happens every time when consumer gets a dependency directly or indirectly using constructor anywhere outside Composition Root. For example in its own constructor or just when it needs it.

class RecipesService {

let repository: RecipesRepository

init() {

self.repository = CoreDataRecipesRepository()

}

}But does that mean that we are not allowed to use constructors at all? Of course not. It depends on what kind of dependency we construct.

Stable & volatile dependencies

There are two kinds of them - stable and volatile. When it comes to stable dependencies we should not worry about constructing them directly inside their consumer. But we should avoid doing that for volatile dependencies.

What is a volatile dependency? Any dependency that requires some specific environment setup, like database or network access. Dependencies that implement nondeterministic behaviour are volatile, for example if they use random numbers, depend on time or implement cryptography. When we expect dependency to be replaced or it is simply not ready yet because it is developed in parallel - it is also volatile.

The symptom of volatile dependencies is that they disable some of loose coupling benefits. If dependency does not let us test, extend, reuse or develop our code in parallel - it should be considered as volatile. Otherwise it is a stable dependency.

So first of all we need to understand if the dependency is volatile or stable and inject it with Dependency Injection patterns when it is volatile.

Bastard injection

The next anti-pattern is called Bastard injection. That happens when we have constructor that lets us provide dependencies for tests and another constructor with default implementations used in production. In Swift we can do that easily with default arguments like in the following example.

class RecipesService {

let repository: RecipesRepository

init(repository: RecipesRepository = CoreDataRecipesRepository()) {

self.repository = repository

}

}From one point this pattern improves testability. The problem of this anti-pattern is in using as a default a foreign default - defined in other module. That makes our code testable, but tightly coupled with another module. If default implementation is local the impact of this anti-pattern is much smaller. Maybe it will be better to refactor it to property injection instead. But when default implementation is foreign we should use constructor injection and do not provide default value for this argument. Instead we should provide it in the Composition Root. This way we don't loose any flexibility but avoid tight coupling with another module.

Service locator

The last anti-pattern I will talk about is a Service Locator. Service Locator is a common name for some service that we can query for different objects that were previously registered in it. It is the most tricky anti-pattern because it can make us feel that everything is absolutely fine. Many developers do not even consider it as an anti-pattern at all. But Service Locator is in fact oposite to Dependency injection.

Let's look at an example:

let locator = ServiceLocator.sharedInstance

locator.register( { CoreDataRecipesRepository() },

forType: RecipesRepository.self)

class RecipesService {

let repository: RecipesRepository

init() {

let locator = ServiceLocator.sharedInstance

self.repository = locator.resolve(RecipesRepository.self)

}

}In this example we have some service that we can access using static property. Then for the type of our dependency we register a factory that produces some concrete instance. Then we ask this service for our dependency when we need it instead of using constructor or property injection.

It seems like Service Locator provides all the benefits of Dependency Injection. It improves extensibility and testability because we can register another implementation of dependency without changing its consumer. It separates configuration from usage and also enables parallel development.

But it has few major drawbacks. It makes dependencies implicit instead of explicit what hides real class complexity. To be able to use this class we now need to know its internal details. We don't see its dependencies and will find out about them only at runtime or by inspecting its implementation or documentation. Also with service locator our code becomes tightly coupled with it. That completely breaks reusability and makes code less maintainable.

For these reasons I tend to think that Service Locator is an anti-pattern. Instead of using it we should define dependencies explicitly, use DI patterns to inject them and use Composition Root to wire them together.

So lets sum up what we have discussed by that point. We discussed that Dependency Injection is used to enable loose coupling what makes our code easier to maintain. We discussed different DI patterns among which constructor injection should be a prefered choise. We discussed what are local and foreign dependencies and what are stable and volatile dependencies. Also we discussed what are common DI anti-patterns that we should avoid.

At this point using DI patterns we've made our dependencies explicit and moved all the configurations in the Composition Root which is already a huge step forward to our goal - loose coupling.

But our code is not yet lossely coupled. The next big step for that is to model dependencies with abstractions. Lets remember one of the SOLID principles.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Dependency Inversion Principle says that high-level code should not depend on lower-level code, they both should depend on abstractions and abstractions should not depend on details. The point is that the class and its dependency should be on the same level of abstraction. If we have some service it should not depend on concrete API repository or data base repository because they belong to lower level layer.

For example we should not depend on API repository implemented with Alamofire or data base repository implemented with CoreData or Realm. Because this will make our code tightly coupled with specific implementation. Instead we should depend on a higher level abstraction. Both service and repository should depend on that abstraction. So the direction of dependency between higher and lower levels is inverted.

And we should follow this principle to have loosly coupled code. Dependency Injection is not just patterns that we discussed before. It requires both patterns and Dependency Inversion Principle to be applied at the same time. Without that we will not get all the benefits of loose coupling.

DI = DI patterns + DIP

It is commonnly said that loose coupling is achieved by programming against interfaces and not to implementations.

Program to an interface, not an implementation (Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software)

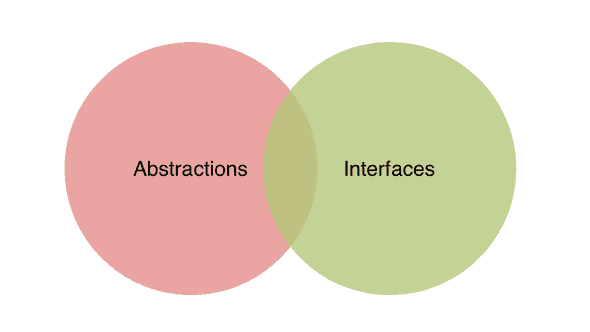

But Dependency Inversion Principle says that it is not about interfaces, but about abstractions. Loose coupling does not mean interfaces or protocols everywhere. Because not always interfaces are good and reusable abstractions.

Program to an

interfaceabstraction

Interface (or a protocol) is just a language construct that we can use to model abstraction. It is a way how our code communicates with it. But it does not make any guarnatee for a good and reusable abstraction which is a key to loose coupling.

Base class can be sometimes as good abstraction as a protocol. Of course most of the time we probably will use protocols to model abstractions. But be careful with introducing protocols everywhere. It can be unneeded level of inderection. And in Swift protocols migth bite sometimes.

Interfaces are not abstractions - Mark Seeman [3]

When you pass a dependency in constructor, or using property or method injection - you should pass it as an abstraction (again, not nececerely using protocol). The same if you use ambinet context. It is not just some shared static instance - it should be an abstraction.

So Dependency Injection and Loose Coupling is achieved not just with Dependency Injection Patterns but also with Dependency Inversion Principle and modeling dependencies with abstractions.

Inversion of Control & DI Containers

But there is also one more step that we can make using another design principle. This principle is called Inversion of Control. It is often seen as a defining characteristic of frameworks.

When we use libraries the flow is "normal" and we call library from our code. But in case of frameworks it is inverted - framework calls our code using different callback methods.

And we can apply this principle for managing dependencies using special frameworks. Usually these frameworks are called Dependency Injection Containers.

There are bunch of different containers available. In fact most of you have used one DI container probably without even knowing that. It is Interface Builder. In Interface Builder we can drag-n-drop any NSObject and reference to it using @IBOutlet through interface or a base class. The same with view controllers. We can think of storyboards and xibs as factories for view controllers. Interface Builder is an example of XML configuration style. It is of course not a full featured DI container and it is not its primary goal but still it can be used for that.

If you go to CocoaPods and search for "dependency injection" you will find a lot of different open source DI containers. Maybe even too many of them. But you will notice that only few of them succeeded and became relatively popular. Let's shortly look at two of them - one that comes from Objective-C world and one from Swift. Typhoon and Dip.

Typhoon

First one, Typhoon, is probably the most popular DI container among Cocoa developers. It has relatively simple and well documented API with lots of powerfull features. It is well maintained and supported and still continues to improve.

In terms of API Typhoon building blocks are objects called assemblies. Here is an example of such assembly interface. It looks like a simple factory.

public class APIClientAssembly: TyphoonAssembly {

public dynamic func apiClient() -> AnyObject {

...

}

public dynamic func session() -> AnyObject {

...

}

public dynamic func logger() -> AnyObject {

...

}

}But in implementation instead of returning a concrete instance of some type like from factory method we return a TyphoonDefinition that describes how that instance should be created when it is requested. What initialiser should be used and with what perameters, what properties should be injected.

public dynamic func apiClient() -> AnyObject {

return TyphoonDefinition.withClass(APIClientImp.self) { definition in

definition.useInitializer(#selector(APIClientImp.init(session:))) {

initializer in

initializer.injectParameterWith(self.session())

}

definition.injectProperty("logger", with: self.logger())

}

}Here we define that APIClient will be created with init(session:) constructor and that it's session argument will be provided by the same assembly. Also we define that logger property will be injected with a logger instance also provided by the same assembly.

We can also define different scopes or lifetime strategies for components. For example with Singleton scope Typhoon will create only one instance of logger.

public dynamic func session() -> AnyObject {

return TyphoonDefinition.withClass(NSURLSession.self) { definition in

definition.useInitializer(#selector(NSURLSession.sharedSession))

}

}

public dynamic func logger() -> AnyObject {

return TyphoonDefinition.withClass(ConsoleLogger.self) { definition in

definition.scope = .Singleton

}

}To get an instance of some type from assembly we first activate it and then just call its interface method. When activated assembly methods will return not TyphoonDefinitions but instances, created based on the rules that we provided.

let assembly = APIClientAssembly().activate()

let apiClient = assembly.apiClient() as! APIClientTo make this work Typhoon uses Objective-C runtime a lot. And in Swift applications using Objective-C runtime looks just not right. We still can use Typhoon in Swift as well as in Objective-C. But there are some problems we will face with:

- Requires to subclass

NSObjectand define protocols with@objc - Methods called during injection should be

dynamic - requires type casting

- not all features work in Swift

- too wordy API for Swift

Typhoon team recently announced that they started to work on pure Swift implementation, and I can't wait to see what they will come up with. But for now I would not use Typhoon in its current state in a pure Swift code base. Especially when there are already few native solutions.

Dip

https://github.com/AliSoftware/Dip

And Dip is one of them. It works only in Swift and it does not require Objective-C runtime at all. In fact it even does not have any references to Foundation, so we can use it on any platform where we can use Swift. It is also type-safe and implementation is not that complicated comparing with Typhoon.

In terms of API it takes approach that is more traditional for DI containers on other platforms and follows "register-resolve" pattern.

Here is the same example that we used for Typhoon.

let container = DependencyContainer()

container.register {

try APIClientImp(session: container.resolve()) as APIClient

}

.resolveDependencies { container, client in

client.logger = try container.resolve()

}

container.register { NSURLSession.sharedSession() as NetworkSession }

container.register(.Singleton) { ConsoleLogger() as Logger }First we register APIClientImp as implementation of APIClient protocol. Container will also resolve contructor argument and when instance is created will set logger property. For session parameter container will use shared url session and for logger it will create a singleton instance.

Then when we need to get the instance of APIClient we simply call resolve method of the container:

let apiClient = try! container.resolve() as APIClientYou may notice that the API is almost the same as we saw in Service Locator. But it is not about API or implementation, it is about how we use it. If you don't want to use container as a Service Locator remember that you should call it only in the Composition Root.

Dip also provides some cool features like auto-wiring. For example we can define logger property to be automatically injected. Container will first create the instance of APIClient and then will use its mirror to find logger property and inject the real instance in it.

class APIClientImp: APIClient {

private let _logger = Injected<Logger>()

var logger: Logger? { return _logger.value }

}Then when we register APIClient using its constructor instead of calling resolve to get a NetworkSession argument we just say that we want to use a first argument passed to the factory closure. Then container will infer its type and resolve it for us.

class APIClientImp: APIClient {

init(session: NetworkSession) { ... }

}

container.register { APIClientImp(session: $0) as APIClient }And that can simplify configuration a lot.

If we compare base features of Typhoon and Dip we will notice that they share most of them. It may seem surprising that almost the same features are possible in Swift even though it does not have powerfull runtime features like in Objective-C. But generics and type inference are in fact enougth for that.

Typhoon Dip

Constructor, property, method injection ✔︎ ✔︎

Lifecycle management ✔︎ ✔︎

Circular dependencies ✔︎ ✔︎

Runtime arguments ✔︎ ✔︎

Named definitions ✔︎ ✔︎

Storyboards integration ✔︎ ✔︎

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Auto-wiring ✔︎ ✔︎

Thread safety ✘ ✔︎

Interception ✔ ︎ ✘

Infrastructure ✔︎ ✘You may ask why do I need to use Typhoon or Dip or any other DI container when I can do the same by my own. There are few reasons I can suggest. They provide easy integration with storyboards, manage components lifecycle for you that can be tricky some times, they can simplify some configurations, Typhoon also provides easy interception using NSProxy and some other additional features.

But remember that DI containers are optional and Dependency Injection is not the same as using DI container.

DI ≠ DI Container

In a new project we may start with it if we want, but in a legacy code base we should first refactor it using Dependency Injection Patterns, Composition Root and Dependency Inversion Principle and then see if DI container is needed or not (in most cases answer will be "no").

If you have complex configurations and you find yourself implementing something like DI container to simplify them or you need some additional features that it provides then probably you will benefit from using already existing implementation. But if you are ok with your own factories - its great and keep using them. Don't use DI container just for the sake of using it.

The same is true for DI itself. Be rational about where to apply it and what parts of your system you need to decouple. Don't try to solve problems that you don't have yet. Maybe you will never have them or the way that you solved them now will not fit when you really face them. At the end DI is just a means to an end, like any other pattern or technology that we use. It is not a goal itself.

In the end I want to mention some usefull resources where you can find more about DI and some related topics.

- "Dependency Injection in .Net" by Mark Seeman

- Mark Seeman's blog

- objc.io Issue 15: Testing. Dependency Injection, by Jon Reid

- "DIP in the wild"

- Non-DI code == spaghetti code?